Growing up, one of our family life’s certainties was that my brother absolutely and categorically did not have a sweet tooth. This made baking for him extremely difficult as he often refused the more sweet or elaborate desserts I made. He did, however, like brownies.

Thus ensued my many year relationship with perfecting the perfect brownie.

He, of course, had a few requirements. First and foremost the brownie had to taste like chocolate. The overriding flavour couldn’t be sugar or flour or heavens forbid – oil. A chocolate brownie had to punch deeply of chocolate and had to have the decadent fattiness that butter brings. So real chocolate (not just cocoa powder) was a must, as was butter (not oil).

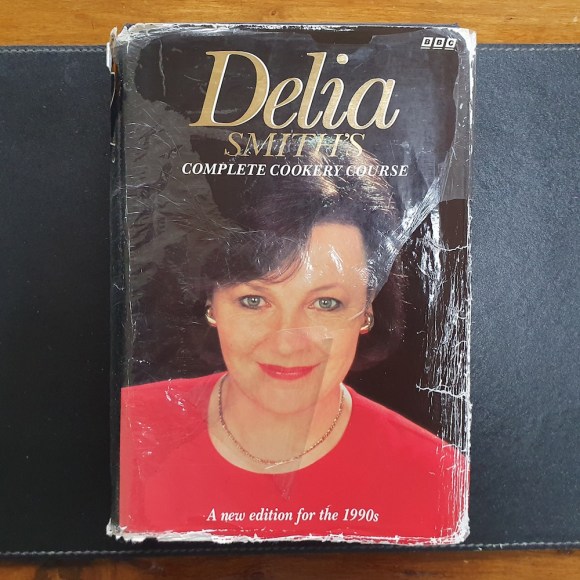

When in doubt, I went to Delia.

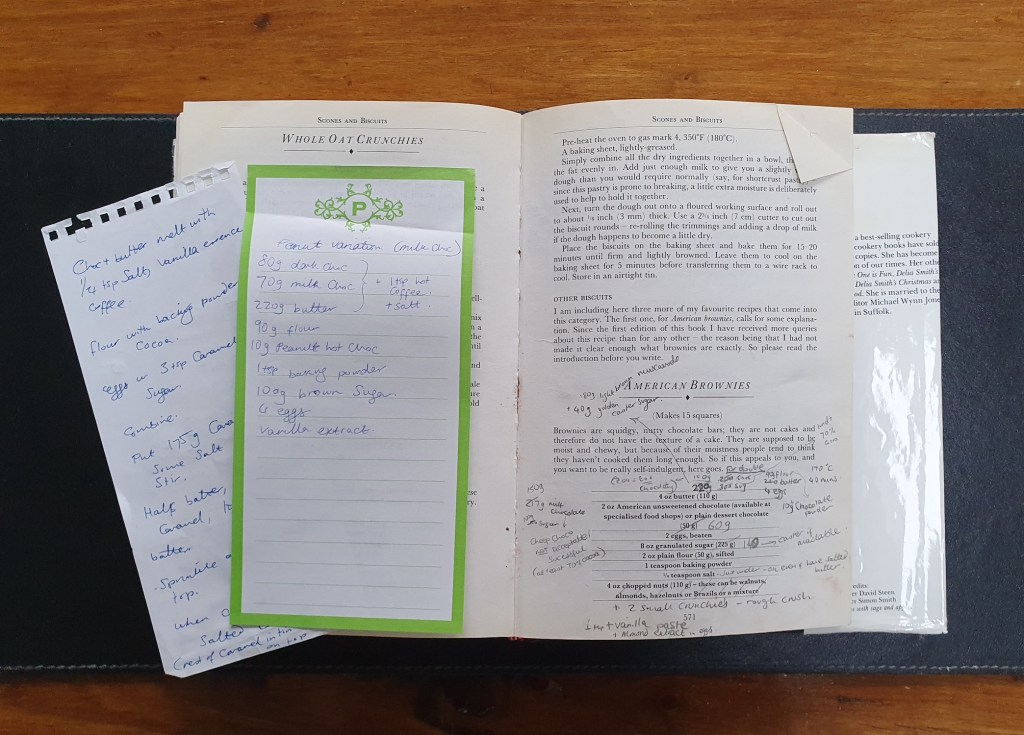

This extremely loved edition of Delia Smith’s Complete Cookery Course (a new edition for the 1990s!) was – and still persists as – a staple in my household. This was the first point of call when setting out to find a brownie recipe for my brother all those years ago. The recipe was good. But yielded a surprisingly small amount and was far too sugary for our tastes.

So I tweaked it.

I cut down the sugar and used fine caster sugar instead of granulated.

I upped the amount of chocolate because it wasn’t quite rich enough.

I reduced the chocolate because it was far too much.

I tried them with muscavado sugar because I wanted more complex toffee-caramel notes which the clean white sugar didn’t give.

I doubled the recipe.

I tried adding almond extract with the eggs.

After Easter, when the only chocolates I had were the £2 large milk chocolate easter eggs, I tried making the brownies with those. (Spoilers – lovely in egg form but not as good in brownies.)

I folded roughly crushed Crunches in the batter before baking (spoilers – really good). I added cocoa powder. I tried a salted caramel version. And a peanut butter one. (Excellent but needs perfecting.)

I even had a favourite brownie baking tin. It was beautiful. It was old and the enamel was chipped in places. It also curved outwards so the base was smaller than the lip of the tin which meant the shallower brownie mixture at the sides overcooked slightly and became chewy, a little bit crispy and a lot delicious. Unfortunately that tin was lost in my parent’s kitchen cull. Goodbye sweet brownie tin! Your brownies were legendary. I shall never forget you.

Over the years I tried, tweaked and re-tweaked it all.

Eventually I came to a recipe that vaguely looked a bit like Delia’s. If you squinted and raised an eyebrow. This recipe, if you’re curious is here: The Brownie.

It’s rich in chocolate and has just enough sweetness to confirm that yes – you are eating a sweet treat, without the whole situation being overpowered by sugar. It’s not squidgy and dense like some brownies are, but the texture is light and somehow melts in your mouth despite it being rich and decadent.

The process to make them is ridiculously simple. This is part of the reason why it sits in the Black Dog series. That, and the fact that a good brownie is one of the ultimate baking food comforts.

If you do try them out, I hope you enjoy eating them as much as we do.

Footnote: For those wondering, yes. Fast forward 20+ years and my brother has since broadened the catalogue of desserts he enjoys. However his favourite sweet treat steadfastly remains my brownies warmed in the oven and topped with a scoop of vanilla ice cream. It’s a family tradition now to make these brownies every Christmas holidays.